To view this page in another language, please click here:

Other Languages

Mayan Civilization

Geography and Landscape

Many dangerous animals occupied this region of the peninsula including the jaguar, the caiman (a fierce crocodile), the bull shark, and many species of poisonous snakes. These animals had to be avoided as the Maya scavenged the forest for foods including deer turkey, peccaries, tapirs, rabbits, and large rodents such as the peca and the agouti. Many varieties of monkeys and quetzal also occupied the upper canopy. The climate of the Highlands greatly contrasted with that of the Lowlands as it was much cooler and drier.

Both the Highlands and the Lowlands were important to the presence of trade within the Mayan civilization. The lowlands primarily produced crops which were used for their own personal consumption, the principle cultigen being maize. They also grew squash, beans, chili peppers, amaranth, manioc, cacao, cotton for light cloth, and sisal for heavy cloth and rope.

The volcanic highlands, however, were the source of obsidian, jade, and other precious metals like cinnabar and hematite that the Mayans used to develop a lively trade. Although the lowlands were not the source of any of these commodities, they still played an important role as the origin of the transportation routes. The rainfall was as high as 160 inches per year in the Lowlands and the water that collected drained towards the Caribbean or the Gulf of Mexico in great river systems. These rivers, of which the Usumacinta and the Grijalva were of primary importance, were vital to the civilization as the form of transportation for both people and materials.

The Maya Culture

Mayan Writing

An elaborate system of writing was developed to record the transition of power through the generations. Maya writing was composed of recorded inscriptions on stone and wood and used within architecture. Folding tree books were made from fig tree bark and placed in royal tombs. Unfortunately, many of these books did not survive the humidity of the tropics or the invasion of the Spanish, who regarded the symbolic writing as the work of the devil.

Four books are known today:

The Dresden Codex

The Madud Codex

The Paris Codex

The Grolier Codex.

The priests followed the ruling class in importance and were instrumental in the recordings of history through the heiroglyphs. The two classes were closely linked and held a monopoly on learning, including writing. The heiroglyphs were formed through a combination of different signs which represented either whole words or single syllables. The information could be conveyed through inscriptions alone, but it was usually combined with pictures showing action to facilitate comprehension.

Political Organization

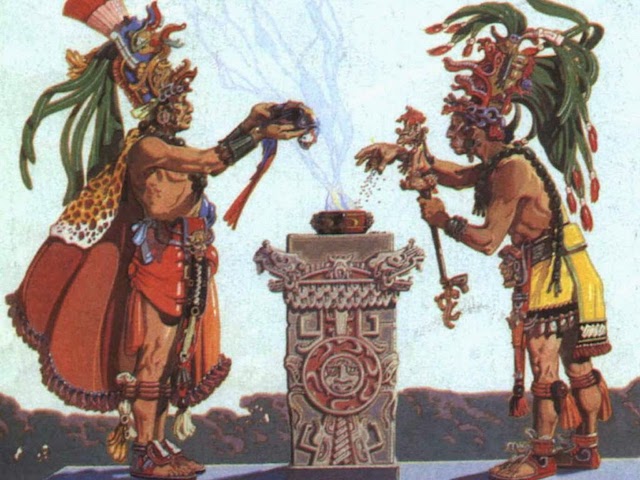

In both the priesthood and the ruling class, nepotism was apparently the prevailing system under which new members were chosen. Primogeniture was the form under which new kings were chosen as the king passed down his position to his son. After the birth of a heir, the kings performed a blood sacrifice by drawing blood from his own body as an offering to his ancestors. A human sacrifice was then offered at the time of a new king's installation in office. To be a king, one must have taken a captive in a war and that person is then used as the victim in his accession ceremony. This ritual is the most important of a king's life as it is the point at which he inherits the position as head of the lineage and leader of the city. The religious explanation that upheld the institution of kingship asserted that Maya rulers were necessary for continuance of the Universe.

Mayan Art

The art of the Maya, as with every civilization, is a reflection of their lifestyle and culture. The art was composed of delineation and painting upon paper and plaster, carvings in wood and stone, clay and stucco models, and terra cotta figurines from molds. The technical process of metal working was also highly developed but as the resources were scarce, they only created ornaments in this media. Many of the great programs of Maya art, inscriptions, and architecture were commissioned by Mayan kings to memorialize themselves and ensure their place in history. The prevailing subject of their art is not anonymous priests and unnamed gods but rather men and women of power that serve to recreate the history of the people. The works are a reflection of the society and its interaction with surrounding people.

One of the greatest shows of Mayan artistic ability and culture is the hieroglyphic stairway located at Copan. The stairway is an iconographical complex composed of statues, figures, and ramps in addition to the central stairway which together port ray many elements of Mayan society. An alter is present as well as many pictorial references of sacrifice and their gods. More importantly than all the imagery captured with in this monument, however, is the history of the royal descent depicted in the heiroglyphs and various statues. The figurine of a seated captive is also representative of Mayan society as it depicts someone in the process of a bloodletting ceremony, which included the accession to kingship. This figure is of high rank as depicted by his expensive earrings and intricately woven hip cloth. The rope collar which would usually mark this man as a captive, reveals that he is involved in a bloodletting rite. His genitals are exposed as he is just about to draw blood for the ceremony.

In the Indian communities, as it was with their Mayan ancestors, the basic staple diet is corn. The clothing worn is as it was in the past. It is relatively easy to determine the village in which the clothing was made by the the type of embroidery, color, design and shape. Mayan dialects of Qhuche, Cakchiquel, Kekchi, and Mam are still spoken today, although the majority of Indians also speak Spanish.

Mysteries of the Mayans

By MICHAEL D. LEMONICKUnraveling the mystery of who the Maya were, how they lived--and why their civilization suddenly collapsed

The crowd at the base of the enormous bloodred pyramid has been standing for hours in the dripping heat of the Guatemalan jungle. No one moves; every eye stays fixed on the building's summit, where the king, his head adorned with feathers, his scepter a two-headed crocodile, is about to emerge from a sacred chamber with instructions from his long-dead ancestors. The crowd sees nothing of his movements, but it knows the ritual: lifted into the next world by hallucinogenic drugs, the king will take an obsidian blade or the spine of a stingray, pierce his own penis, and then draw a rope through the wound, letting the blood drip onto bits of bark paper. Then he will take the bark and set it afire, and out of the rising smoke a vision of a serpent will appear to him.

When the king finally emerges, on the verge of collapse, he reaches under his loincloth, displays a bloodstained hand and announces the ancestors' message--the same message he has received so many times in the past: "Prepare to go to war." The crowd erupts in wild cheers. The bloodletting has barely begun.

Who were the Maya, the people who built and later abandoned these majestic pyramids scattered around Central America and who enacted these bizarre rites? The question has piqued scientists across a broad swath of disciplines ever since an American lawyer and explorer named John Lloyd Stephens stumbled across something strange in the Honduran jungle. In Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan (1841), Stephens impressionistically described what was later identified as the ruined Maya city of Copan: "It lay before us like a shattered bark in the midst of the ocean, her masts gone, her name effaced, her crew perished, and none to tell whence she came, to whom she belonged, how long on her voyage, or what caused her destruction."

More than 150 years later, the Maya seem less inscrutable than they did to Stephens, the man who discovered, or rediscovered, what they had left behind. Archaeologists have long known that the Maya, who flourished between about A.D. 250 and 900, perfected the most complex writing system in the hemisphere, mastered mathematics and astrological calendars of astonishing accuracy, and built massive pyramids all over Central America, from Yucatan to modern Honduras. But what researchers have now found among these haunting irruptions of architecture may be, among other things, reasons for admonishing today's world: at a time when tribal fratricide is destroying Bosnia and farmers are carving through the rain forest, the lessons yielded by the Maya have a disturbing resonance.

The latest discovery, announced just this week, underscores how quickly Maya archaeology is changing. Four new Maya sites have been uncovered in the jungle-clad mountains of southern Belize, in rough terrain that experts assumed the Maya would have shunned. Two of the sites have never been looted, which will provide researchers with a wealth of clues to the still largely unsolved puzzle of who the Maya were--and the mystery of how and why their civilization collapsed so catastrophically around the year 900. Of course, considerable mysteries persist and always will. "I wake up almost every morning thinking how little we know about the Maya," says George Stuart, an archaeologist with National Geographic. "What's preserved is less than 1% of what was there in a tropical climate."

Such limited and often puzzling physical evidence has not deterred growing legions of archaeologists, art historians, epigraphers, anthropologists, ethnohis torians, linguists and geologists from making annual treks to Maya sites. Propelled by a series of dramatic discoveries, Mayanism has been transformed over the past 30 years from an esoteric academic discipline into one of the hottest fields of scientific inquiry--and the pace of discovery is greater today than ever.

Among the already addicted, Mayamania is easy to explain. Says Arthur Dem arest, a Vanderbilt University archaeologist who for the past four years has led a team of researchers unearthing the remains of Dos Pilas, a onetime Maya metropolis in northern Guatemala: "You've got lost cities in the jungle, secret inscriptions that only a few people can read, tombs with treasures in them, and then the mystery of why it all collapsed."

The explosion of information has led to a comparable explosion of theorizing about the Maya, along with inevitable, often vehement, disagreements over whose ideas are right. Nevertheless, a consensus has begun to emerge among Mayanists. Among the first myths about this population to be debunked is that they were a peaceful race. Experts now generally agree that warfare played a key role in Maya civilization. The rulers found reasons to use torture and human sacrifice throughout their culture, from religious celebrations to sporting events to building dedications. "This has come as something of a shock to many Mayanists," says Carlos Navarrete, a leading Mexican anthropologist.

Uncontrolled warfare was probably one of the main causes for the Maya's eventual downfall. In the centuries after 250--the start of what is called the Classic period of Maya civilization--the skirmishes that were common among competing city-states escalated into full-fledged, vicious wars that turned the proud cities into ghost towns.

Among the first modern Westerners to be captivated by the Maya were the American Stephens and English artist Frederick Catherwood, who started in 1839 to bushwhack their way into the Central American rain forest to gaze at the monumental ruins of Copan, Palenque, Uxmal and other Maya sites. The book Stephens wrote about his trek was an enormous popular success and sparked others to follow him and Catherwood into the jungle and into musty Spanish colonial archives. Over the next half-century, researchers uncovered, among other things, the Popol Vuh (the sacred book of the Quiche Maya tribe) and the Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan, an account of Maya culture during and immediately after the 16th century Spanish conquest written by the Roman Catholic bishop Diego de Landa. By the 1890s, Alfred Maudslay, an English explorer, was compiling the first comprehensive catalog of Maya buildings, monuments and inscriptions in the major known cities, and the first excavations were under way.

With all this data, 19th century scholars began trying to decipher the hieroglyphic script, reconstruct Maya history and figure out what caused the civilization to fall apart. In the absence of any historical context, though, speculation tended to run a little wild. Some ascribed the monumental buildings to survivors of the lost continent of Atlantis; others insisted they were the work of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, or the Egyptians, the Phoenicians, the Chinese, or even the Javanese.

The first half of the 20th century brought more excavations and more cataloging--but still only scratched the surface of what was to come. By 1950 the field was dominated by J. Eric Thompson and Sylvanus Morley of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. Both are still revered as brilliant archaeologists, but some of their theories have been overturned by new evidence. Among their now outdated ideas: that the city centers of the Classic Maya were used primarily for ceremonial purposes, not for living; hieroglyphic texts described esoteric calendrical, astronomical and religious subjects but never recorded anything as mundane as rulers or historical events; slash-and-burn agriculture was the farming method of choice; and, of course, the Maya lived in blissful coexistence with one another.

Morley and Thompson presumed that certain practices of the ancient Maya could be deduced from those of their descendants. Modern scientists are more rigorous; besides, they have the advantage of sophisticated technology, like radiocarbon dating, which can help test their theories.

Near the Mexican border of Guatamala, in the Maya city of Dos Pilas and the surrounding Petexbatun region, Arthur Demarest's excavations have put him at the forefront of the revisionists. He divides the history of the region into two periods: before 761 and after. Before that year, he says, wars were well-orchestrated battles to seize dynastic power and procure royal captives for very public and ornate executions. But after 761, he notes, "wars led to wholesale destruction of property and people, reflecting a breakdown of social order comparable to modern Somalia." In that year the king and warriors of nearby Tamarindito and Arroyo de Piedra besieged Dos Pilas. Says Demarest: "They defeated the king of Dos Pilas and probably dragged him back to Tamarindito to sacrifice him." The reason for the abrupt change in the Maya's battleground behavior, he suspects, was that the ruling elite had grown large enough to produce intense rivalries among its members. Their ferocious competition, which exploded into civil war, may have been what finally triggered the society's breakdown. Similar breakdowns, he believes, happened in other areas as well.

Arlen and Diane Chase, archaeologists at the University of Central Florida, believe their work at Caracol, in present-day Belize, also shows that escalating warfare was largely responsible for that ancient city's abrupt extinction. Among the evidence they cite: burn marks on buildings, the uncharacteristically unburied body of a six-year-old child lying on the floor of a pyramid, and an increase in war imagery on late monuments and pottery. "Of course we found weapons too," says Arlen.

While many Mayanists agree that wars contributed to the collapse, no one thinks they were the whole story. Another factor was overexploitation of the rain-forest ecosystem, on which the Maya depended for food. University of Arizona archaeologist T. Patrick Culbert says pollen recovered from underground debris shows clearly that "there was almost no tropical forest left."

Water shortages might have played a role in the collapse as well: University of Cincinnati archaeologist Vernon Scarborough has found evidence of sophisticated reservoir systems in Tikal and other landlocked Maya cities (some of the settlements newly discovered this week also have reservoirs). Since those cities depended on stored rainfall during the four dry months of the year, they would have been extremely vulnerable to a prolonged drought.

Overpopulation was another problem. On the basis of data collected from about 20 sites, Culbert estimates that there were as many as 200 people per sq km in the southern lowlands of Central America. Says Culbert: "This is an astonishingly high figure; it ranks up there with the most heavily populated parts of the pre-industrial world. And the north may have been even more densely populated."

One inevitable consequence of overpopulation and a disintegrating agricultural system would be malnutrition--and in fact, some researchers are beginning to find preliminary evidence of undernourishment in children's skeletons from the late Classic period. Given all the stresses on Maya society, says Culbert, what ultimately sent it over the edge "could have been something totally trivial--two bad hurricane seasons, say, or a crazy king. An enormously strained system like this could have been pushed over in a million ways."

What sorts of lessons can be drawn from the Maya collapse? Most experts point to the environmental messages. "The Maya were overpopulated and they overexploited their environment and millions of them died," says Culbert bluntly. "That knowledge isn't going to solve the modern world situation, but it's silly to ignore it and say it has nothing to do with us." National Geographic archaeologist George Stuart agrees. The most important message, he says, is "not to cut down the rain forest." But others are not so sure. Says Stephen Houston, a hieroglyphics expert from Vanderbilt University: "I think we should be careful of finding too many lessons in the Maya. They were a different society, and the glue that held them together was different."

Just how different the Maya were is clear from their everyday lives, on which archaeologists are increasingly focusing. From the contents of graves and burial caches, the architecture of ordinary houses, and scenes painted on pottery, Demarest and others are learning what an average Maya day was like.

The typical Maya family (averaging five to seven members, archaeologists guess) probably arose before dawn to a breakfast of hot chocolate--or, if they weren't rich enough, a thick, hot corn drink called atole--and tortillas or tamales. The house was usually a one-room hut built of interwoven poles covered with dried mud. Meals of corn, squash and beans, supplemented with the occasional turkey or rabbit, were probably eaten on the run.

During the growing season, men would spend most of the day in the fields, while women usually stayed closer to home, weaving or sewing and preparing food. At the end of the day the family would reconvene at home, where the head of the household might perform a quick bloodletting, the central act of piety, accompanied by prayers and chanting to the ancestors. Days that were not devoted to agriculture might be spent building pyramids and temples. In exchange for their toil, the people expected to attend royal marriages and ceremonies marking important astrological and calendrical events. At these occasions the king might perform a bloodletting, sacrifice a captive or preside over a ball game--the losers to be beheaded, or sometimes tied in a ball and bounced down the stone steps of a pyramid. Like modern-day hot-dog vendors, craftsmen and farmers might show up for these games to set up stands and barter for pots, cacao and beads.

The Maya also had a highly devel oped--and to modern eyes, highly bi zarre--aesthetic sense. "Slightly crossed eyes were held in great esteem," writes Yale anthropologist Michael Coe in his book The Maya. "Parents attempted to induce the condition by hanging small beads over the noses of their children." The Maya also seemed to go in for shaping their children's skulls: they liked to flatten them (although this may have simply been the inadvertent result of strapping babies to cradle boards) or squeeze them into a cone. Some Mayanists speculate that the conehead effect was the result of trying to approximate the shape of an ear of corn.

The Maya filed their teeth (it's unclear whether they used an anesthetic), sometimes into a T shape and sometimes to a point. They also inlaid their teeth with small, round plaques of jade or pyrite. According to Coe, young men painted themselves black until marriage and later engaged in ritual tattooing and scarring.

Information about the Maya has come not just from physical objects but also from the elaborate hieroglyphics they left behind. Indeed, the study of Maya writing has become a coequal--and sometimes competitive--path of inquiry. For some reason it has attracted more than its share of amateurs. In the early 1970s, "discoveries came at the pace of a raging prairie fire," writes Coe in his latest book, Breaking the Maya Code. Former University of South Alabama art teacher Linda Schele burst into the epigraphical world. On a 1970 visit to Mexico, she was mesmerized by the ruins at Palenque. Three years later, she was accomplished enough to collaborate with two others in a mind-boggling feat of decipherment: during a conference at modern Palenque, the trio took a mere 2 1/2 hours to decode the history of Palenque and its rulers from the beginning of the 7th century to its fall around the late 8th century--and got it right.

How was this possible? Because, say the professionals, deciphering glyphs depends as much on intuition and instinct as it does on knowledge of a given writing system. Insight can strike like lightning. Says Schele, now an art historian at the University of Texas at Austin: "These moments of clarity are just extraordinary. The greatest thrills of my career came in those moments when the inscription becomes clear and we suddenly understand the humans who created this legacy for the first time."

The Palenque decipherment work began an epigraphic revolution. Since then, the field has been blessed with a number of young, gifted epigraphers, including Stephen Houston, 34, and David Stuart, 28, who began his career as a child. The son of Maya archaeologists George and Gene Stuart, he made his first trip to Maya ruins at the age of three, and by 1984, at 18, was so skilled at deciphering glyphs that he became the youngest recipient ever of a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant. Stuart's next project is nothing less than cataloging every known Maya inscription, a task he guesses could take him the rest of his life. "There is at least another century of work; it will go on long after I'm gone," he says.

Like most official records, glyphs undoubtedly contain a healthy dose of propaganda. Imagine, argues Richard Leven thal, director of UCLA's Institute of Archaeology, that you tried to understand the Gulf War by reading Saddam Hussein's pronouncements. Says Arlen Chase: "You get this real warped view of what Maya politics and Classic society look like if you just use epigraphy. It's important, but archaeology is the only way to test it." Observes Houston: "Of course it's propaganda, but to jump from that to a blanket dismissal is preposterous."

The argument over how to interpret Maya writing--along with arguments over just about every other aspect of Maya archaeology--won't be resolved anytime soon. New discoveries are constantly reinventing the conventional wisdom. At Ca racol, for example, the Chases have uncovered an unprecedented 74 relic-filled tombs; their location, in living areas, supports the idea of ancestor worship, and the number of burial chambers provides evidence, the Chases think, that the Maya had a large, prosperous "middle class."

In Dos Pilas, Arthur Demarest is turning his attention to garbage piles. "Those are the most important finds," he says, "not the tombs, because you find everything they ate, their tools--a real cross-section of life, in really good preservation." A colleague plans to study the chemical composition of ancient soil and pollen samples and exhumed human bones to learn more about the Maya diet, common diseases, agricultural practices and even what the climate was like.

As they excavate deeper into the Maya past, archaeologists and other scientists are still struggling to make sense of this legacy of triumph and self-destruction. And there usually comes a point when a Mayanist has to decide how to draw joyful inspiration from the culture's destiny. "It's a very rare thing for the past to be a source of deep-seated pessimism," says David Freidel, an anthropologist at Southern Methodist University. So Freidel has come up with this way to think of the Maya: "When I see the past, what I see are not just the failures of human effort, of human imagination, but that unquenchable desire to make of life a meaningful thing."

By GUY GARCIA PALENQUE

With reporting by Laura Lopez/San Cristobal de las Casas

A tour guide at the legendary ruins of Palenque in Chiapas, Mexico, likes to tell the story. A tourist, after staring in awe at the towering pyramids, turned to the guide and said, "The buildings are beautiful, but where did all the people go?" "Of course, she was talking to a Maya," the guide says, shaking his head at the irony. "We're still here. We never left."

The exchange illustrates a living paradox at the heart of the Maya puzzle: even as scientists continue to investigate the mysterious eclipse of the classic Maya empire, the Maya themselves are all around them. An estimated 1.2 million Maya still live in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, and nearly 5 million more are spread throughout the Yucatan Peninsula and the cities and rural farm communities of Belize, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. Ethnically, they are derived from the same people who created the most exalted culture in Mesoamerica. Yet the thousands of visitors who come each year to admire the imposing temples of Palenque might be shocked to know the ignominious fate of the Maya's modern-day descendants.

Centuries of persecution and cultural isolation have turned the Maya into impoverished outcasts in their own land. At best, they are often reduced to tourist attractions; for a little money, Mexico's Lacandon Indians, for instance, will display their traditional white cotton shikur and long black hair. But condescension is the mildest of the abuses suffered by today's Maya. In a 1992 report on the indigenous peoples of the Americas, Amnesty International cited dozens of human-rights violations carried out by Mexican authorities against the Maya people of Chiapas: they include an incident in 1990 when 11 Maya were tortured after being arrested during a land dispute, and another one two years ago when 100 Maya were beaten and imprisoned for 30 hours without food or medical attention. In Guatemala's 30-year-old civil war, it has been the Maya who have been the primary victims of the military's antiguerrilla campaigns in the highlands, which have left 140,000 Guatemalans dead or missing. In some cases, government troops have burned entire Maya villages.

The systematic subjugation of the Maya dates back to the Spanish Conquest of the early 16th century, when Catholic missionaries outlawed the Maya religion and burned all but four of their sacred bark-paper books. Indians who were not killed in battle or felled by European diseases were forced to work on colonial plantations, often as slaves. Bands of Maya rebels, known to be ferocious fighters, resisted pacification for almost 400 years, first under the Spanish occupation and then under the Mexican army after Mexico became independent.

Despite this history of defiance--or maybe, in some cases, because of it--the Maya continued to be targets of abuse even after being incorporated into the family of Central American nations. As recently as 20 years ago, Maya peasants carrying chickens or peanuts to the town market in San Cristobal de las Casas were in danger of having their wares snatched away by non-Indian women, or "Black Widows." And though the town's economy depended on trade with the Indians, Maya found walking the streets at night would be thrown into jail and fined.

Today, despite government decrees that guarantee equal rights for Indians and the new presidency in Guatemala of human-rights champion Ramiro de Leon Carpio, indigenous peoples like the Maya remain at the bottom rung of the political and economic ladder. In Chiapas, where the natives speak nine different languages, literacy rates are about 50%, compared with 88% for Mexico as a whole. Infant mortality among the Maya is 500 per 1,000 live births, 10 times as high as the national average. And 70% of the Indians in the countryside lack access to potable water.

In these sorry conditions, many Maya have seized on their old ways to make sense of their modern lives. In the remote highlands of Guatemala and Mexico, where the rugged terrain has held the outside world at bay, contemporary Maya still practice many of the same rituals that were performed by their ancestors 4,000 years ago. Maya weavers embroider their wares with diamond motifs that are virtually identical to the cosmological patterns depicted on the lintels of ancient temples at Yaxchilan and other Maya sites. By marking their clothing with the symbols of their ancestors, the Maya artisans build a material link to pre-Columbian gods--and the indelible spirit of their cultural past. "Depictions of everyday life do not occur in the weaving," notes Walter F. Morris Jr., a Seattle-based anthropologist and author of Living Maya. "It's always something supernatural, something dreamt, something you can only see in dreams."

Chiapas, Yaqui Indians follow two brothers who, guided by the spirit voices of macaws, retake the high country from the Hispanics who scorn and oppress them. In Alaska, a Yupik woman knows how to down airplanes by hexing television sets with a fox pelt. Near Tucson, two half-breed witches, elderly twin sisters, import cocaine to undermine the enemy and buy guns to store at their fortified ranch. Wherever it is shown, the white society is murderous, corrupt, mad with greed and hideously perverted. Among the white characters, and quite typical of the rest, are a federal judge who has sex with his basset hounds and a reptilian homosexual who steals the baby of a drug-soaked stripteaser for use in a torture video.

The ruling society has gone septic and sterile. Lecha, one of the twin witches, who can find lost objects and dead bodies, notices that "affluent, educated white people...sought [her] out in secret. They all had come to her with a deep sense that something had been lost...lottery tickets, worthless junk bonds or lost loved ones; but Lecha knew the loss was their connection with the earth." Later an Indian orator picks up the theme. Spirit voices direct white mothers "to pack the children in the car and drive off hundred-foot cliffs or into flooding rivers...The spirits whisper in the brains of loners, the crazed young white men with automatic rifles who slaughter crowds in shopping malls or school yards as casually as hunters shoot buffalo."

The author's sentences have a drive and a sting to them. But the receptacle of her crowded, raging, enormously long book swirls with half-digested revulsion, half-explained characters and, a white elitist must add, more than a little self-righteousness. The novel's long first half is a dull headache, because most of the dozen or more narrators, none of whom knows what is going on, are drunk, doped or crazy.

Yet angry prophets can't be expected to write neat, button-down denunciations. Old Indian legends, the author relates, say that after a very long time, the cruel and greedy white conquerors will weaken and vanish. Her intention is to bring readers to the point at which this is about to happen, and her success is far more troubling than her failure.

Chiapas, Mexico, for instance, are not threatened by native Lacandon practices but by the more commercial agricultural practices of encroaching peasants, according to James Nations of Conservation International in Washington. Many indigenous farmers in Asia and South America manage to stay on one patch of land for as long as 50 years. As nutrients slowly disappear from the soil, the farmers keep switching to hardier crops and thus do not have to clear an adjacent stretch of forest.

Westerners have also come to value traditional farmers for the rich variety of crops they produce. By cultivating numerous strains of corn, legumes, grains and other foods, they are ensuring that botanists have a vast genetic reservoir from which to breed future varieties. The genetic health of the world's potatoes, for example, depends on Quechua Indians, who cultivate more than 50 diverse strains in the high plateau country around the Andes mountains in South America. If these natives switched to modern crops, the global potato industry would lose a crucial line of defense against the threat of insects and disease.

Anthropologists studying agricultural and other traditions have been surprised to find that people sometimes retain valuable knowledge long after they have dropped the outward trappings of tribal culture. In one community in Peru studied by Christine Padoch of the Institute of Economic Botany, peasants employed all manner of traditional growing techniques, though they were generations removed from tribal life. Padoch observed almost as many combinations of crops and techniques as there were households. Similarly, a study of citified Aboriginal children in Australia revealed that they had far more knowledge about the species and habits of birds than did white children in the same neighborhood. Somehow their parents had passed along this knowledge, despite their removal from their native lands. Still, the amount of information in jeopardy dwarfs that being handed down.

Lending a Hand

There is no way that concerned scientists can move fast enough to preserve the world's traditional knowledge. While some can be gathered in interviews and stored on tape, much information is seamlessly interwoven with a way of life. Boston anthropologist Jason Clay therefore insists that knowledge is best kept alive in the culture that produced it. Clay's solution is to promote economic incentives that also protect the ecosystems where natives live. Toward that end, Cultural Survival, an advocacy group in Cambridge, Mass., that Clay helped establish, encourages traditional uses of the Amazon rain forest by sponsoring a project to market products found there.

Clay believes that in 20 years, demand for the Amazon's nuts, oils, medicinal plants and flowers could add up to a $15 billion-a-year retail market--enough so that governments might decide it is worthwhile to leave the forests standing. The Amazon's Indians could earn perhaps $1 billion a year from the sales. That could pay legal fees to protect their lands and provide them with cash for buying goods from the outside world.

American companies are also beginning to see economic value in indigenous knowledge. In 1989 a group of scientists formed Shaman Pharmaceuticals, a California company that aims to commercialize the pharmaceutical uses of plants. Among its projects is the development of an antiviral agent for respiratory diseases and herpes infections that is used by traditional healers in Latin America.

An indigenous culture can in itself be a marketable commodity if handled with respect and sensitivity. In Papua New Guinea, Australian Peter Barter, who first came to the island in 1965, operates a tour service that takes travelers up the Sepik River to traditional villages. The company pays direct fees to villages for each visit and makes contributions to a foundation that help cover school fees and immunization costs in the region. Barter admits, however, that the 7,000 visitors a year his company brings through the region disrupt local culture to a degree. Among other things, native carvers adapt their pieces to the tastes of customers, adjusting their size to the requirements of luggage. But the entrepreneur argues that the visits are less disruptive than the activities of missionaries and development officials.

There are other perils to the commercial approach. Money is an alien and destabilizing force in many native villages. A venture like Barter's could ultimately destroy the integrity of the cultures it exhibits if, for example, rituals become performances tailored to the tourist business. Some villages in New Guinea have begun to permit tourists to visit spirit houses that were previously accessible only to initiated males. In Africa villages on bus routes will launch into ceremonial dances at the sound of an approaching motor. Forest-product concerns like those encouraged by Cultural Survival run the risk of promoting overexploitation of forests, and if the market for these products takes off, the same settlers who now push aside natives to mine gold might try to take over new enterprises as well.

Still, economic incentives already maintain traditional knowledge in some parts of the world. John and Terese Hart, who have spent 18 years in contact with Pygmies in northeastern Zaire, note that other tribes and villagers rely on Pygmies to hunt meat and collect foods and medicines from the forests, and that this economic incentive keeps their knowledge alive. According to John Hart, the Pygmies have an uncanny ability to find fruits and plants they may not have used for years. Says Hart: "If someone wants to buy something that comes from the forest, the Pygmies will know where to find it."

Restoring Respect

Preserving tribal wisdom is as much an issue of restoring respect for traditional ways as it is of creating financial incentives. The late Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy put his prestige behind an attempt to convince his countrymen that their traditional mud-brick homes are cooler in the summer, warmer in the winter and cheaper than the prefabricated, concrete dwellings they see as modern status symbols.

Balick has made it part of his mission to enhance the status of traditional healers within their own communities. He and his colleagues hold ceremonies to honor shamans, most of whom are religious men who value respect over material reward. In one community in Belize, the local mayor was so impressed that American scientists had come to learn at the feet of an elderly healer that he asked them to give a lecture so that townspeople could learn about their own medical tradition. Balick recalls that this healer had more than 200 living descendants, but that none as yet had shown an interest in becoming an apprentice. The lecture, though, was packed. "Maybe," says Balick, "seeing the respect that scientists showed to this healer might inspire a successor to come forward."

Such deference represents a dramatic change from past scientific expeditions, which tended to treat village elders as living museum specimens. Balick and others like him recognize that communities must decide for themselves what to do with their traditions. Showing respect for the wisdom keepers can help the young of various tribes better weigh the value of their culture against blandishments of modernity. If young apprentices begin to step forward, the world might see a slowing of the slide toward oblivion.

A MAYAN LIFE

first novel ever by a Mayan writer

The Mayan Epigraphic Database Project

Maya Indians No Longer Hide Ancient Faith Behind Catholicism

![]() Return to Indigenous Peoples' Literature

Return to Indigenous Peoples' Literature

Compiled by: Glenn Welker

ghwelker@gmx.com

This site has been accessed 10,000,000 times since February 8, 1996.